The opening ceremony for the postponed Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympic Games is due to take place later today.

Perfect timing then to take a look at how timekeeping at the Olympics has changed over the years…

When the Modern Olympics began in 1896, event timekeeping was performed using handheld mechanical stopwatches, very similar to the ones still available today. Whilst accuracy was of course important, it’d be fair to say that timekeeping wasn’t to the standard we’re accustomed to now. Timekeepers for events would use their own stopwatches, timing to 1/5th or 1/4th of a second, rather than using a common standard calibrated stopwatch that’d time events consistently.

Numerous officials at the start and finish lines would time each event and then collectively figure out the results after the race, in some cases taking averages of times to determine the winner. The handheld stopwatch would actually continue to be used for decades, right up until the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, but technology had started to change the timekeeping process well before they were phased out.

In the 1912 Stockholm games, a semi-automated system was introduced for some athletics events. A stopwatch timing each competitor was placed at the finish line and connected to an electromagnetic circuit. The starters pistol (also connected to the electromagnetic circuit) would start the race and all of the stopwatches simultaneously. Timekeepers positioned at the finish line would then manually stop each stopwatch when their assigned competitor crossed the finish line. When the first competitor crossed the line, a camera was triggered by the lead timekeepers stopwatch, taking the Olympics first semi-automatic ‘photo-finish’.

On an unrelated note – the 1912 games were also notable for being the first to feature events for architecture, literature, music, painting and sculpture. A “Pistol Duelling” event from the previous Olympics in 1908 however didn’t make a return (presumably because there weren’t enough competitors left to take part!).

For the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles, a single Swiss watch-maker from Omega delivered 30 calibrated chronographs to the Games. In contrast, more recent Games have required hundreds of professional timekeepers with specialist timing equipment along with servers, scoreboards and miles of cabling – all weighing up to 450 tonnes.

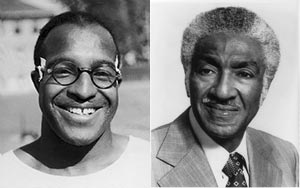

During those 1932 games, a “Two Eye Camera” was also introduced for athletics events. This camera simultaneously recorded the finish line and a chronometer at 128 frames per second, dramatically improving accuracy. Official timing for athletics had already improved to 1/10th of a second and that year, the new “Two Eye Camera” technology would prove decisive in deciding the winner of the men’s 100m final. It was a very close, controversial final that even caused the rules to be changed the following year. The story of the 1932 final and footage from the “Two Eye Camera” can be found below.

By 1968, all timekeeping was performed both electronically and manually, with the electronic timing being deemed the official result. The introduction of digital timing ushered in a new era for accuracy. At the following Olympics, official results for events started being declared to 1/100th of a second. Even then, timing equipment in use for swimming events was capable of recording to 1/1000th of a second. Despite it being the standard today in other sports such as Formula 1, as far as we’re aware there are still no plans to declare all timed events to the thousandth.

Other advances in timing have continued though. For the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, photo finish cameras for athletics events recorded the finish line at 3,000 frames per second – three times quicker than the cameras used at the 1996 games in Atlanta.

Swiss luxury watchmaker Omega has served as official timekeeper for the Olympics on 27 occasions and will again carry out the task in Tokyo. For the 2016 Olympics in Rio, Omega produced an interesting history of their timekeeping activities at the Olympics, including the controversial story of the 1960 Men’s Freestyle Swimming final, where the competitor setting the fastest time… came second. The film is an interesting watch and illustrates perfectly how less than 1/100th of a second can sometimes make all the difference.